Is China's High Speed Railway System Massively Overbuilt, just Overbuilt, or will be Overbuilt?

For the glory of High Speed Rail... this might be the start of a collection of posts.

A subscriber pointed to me a post on Pekingnology translating a Chinese article written by an esteemed 85 year old Chinese economic geographer Lu Dadao (陆大道)1. The article of note is 高铁辉煌,高铁问题如何了?or translated by Pekingnology as “The Glory of High Speed Rail: What About Its Problems?”. You can read the translated text below.

Or you can read the unadulterated Hanzi version straight from Mr. Land Transportation himself.

The contributing authors of the translated piece noted that it was:

lengthy, comprehensive, sharp — and at times even indignant

The author in this piece was lengthy, sharp — (*gasp* emdash) and ironically described as “at times even indignant”. Ironic because I don’t think Mr. Lu, hereinto referred to as the Author, was fair to China’s HSR system in his critique.

House cleaning

I will state for the record a subscriber (so like, share and subscribe) alerted me of this translated article hours after it was published, followed by Reece Martin of Next Metro fame asking for my thoughts on the translated text a few days later. During the long process of writing this a few additional subscribers reached out asking for my comment. I think it is important to set the record straight here not because China and/or its massive high speed railway system is infallible or something (it isn’t).

After translation the Author’s negative coverage has become used in two ways overseas:

“Experts” that use the critique China’s high speed railway system as a talking point to discredit the entire concept of high speed rail in their countries. As such the Author’s article has been a commonly used as a citation in their protestations against high speed rail since the translated version was published weeks ago.

Others still, strictly motivated by ideology, would use the Author’s article as a general dig against China’s model of development.

Uniquely some use the Author’s article to disprove of both China and high speed rail at the same time (they are special). Due to the contrived nature of the above two perspectives upholding the Author’s article for validation, hopefully the Author’s article is factually robust enough to support whatever high speed rail development they are arguing against in their own countries. Sadly this does not seem to be the case, as upon closer inspection, the Author’s article is riddled with questionable opinions, wild conjecture and most damningly, technical errors. Anyone using the Author’s article to argue against high speed rail should not be proud of themselves because it shows they did not do any research and are highly susceptible to very willingly take things at face value when it conveniently fits their narrative. They are not experts and their options derived from support of the Author’s article should be discarded.

In this initial post, I will focus on the more technical aspects of the article, the Author goes deep into finance and economics in many sections. My observation is many of these finance and economics opinions the Author gives tends to have a very narrow focus and is overall quite dismissive of broader benefits HSR can bring, a common skeptical slant the Author has. Maybe a further discussion on this can be done in a later part 2. Regardless, I will focus on the technical side in my review in this part 1. Why? Well, my view is that if you are going to (rightfully) criticize something, I expect you to get the facts at hand correct. The goes for overseas commentary citing this Author’s article to discredit the CRH system or oppose HSR schemes in their own country. Again, if you uncritically praised this Author’s article and/or used it a proof for your own arguments against other high speed railway schemes (whatever they may be) perhaps some lateral reading on the topic is in order for you. Doubly true if you claim to be a “transportation expert” using what Mr. Lu has produced here to support your argument. As broadly speaking, the Author makes many incorrect assumptions about how railways work or makes mistakes on basic Chinese geography. The article seems to be a long distillation of passages the Author has previously posted, as such it is long but I will review a few sections in this part 1, starting at the top.

For the Glory of High Speed Rail

The Author begins with a short general overview of recent general Chinese transportation and economic history. Then quickly dives to “specifically address the issues arising in China’s HSR planning and construction from the perspectives of rationality and economy.”, where he further elaborates in more detail on China’s high speed railway development, touching on initial transportation planning rationales. Reading Chinese high speed railway history from his perspective, I get the feeling that the Author’s views on China’s entire high speed railway program can be summarized as: “problematic waves and waves of irrational expansion, punctuated by eye watering statistics” which they use to drive their high speed railway overbuilding thesis with statements such as “70,000 km of high speed railway in China by 2035”, mirroring sensationalist Western media headlines, which also get China’s high speed railway development wrong.

He ends the section promising to “tackle all these issues, albeit from a peripheral angle, and can only expose a fraction of the full picture.”. I will also do the same in multiple parts. With that out of the way, the Author continues with a section on…

What is HSR?

This section is a bit of a contrived mess. The Author basically spends several paragraphs explaining that faster trains mean more expensive tracks. TL;DR, to the Author, high speed railways are just faster more expensive conventional railways. Yes, but that does not answer the question. What is the definition of HSR we will be using? What is the definition other people using? Is high speed rail a railway designed for speeds of +200kph? +250kph? +300kph? What if it is designed to support 300kph operations but currently runs passenger trains at 200kph and reserved for freight operations? Can passenger and freight trains both run on it? The Author also does not properly define what conventional railways are, noting a conventional railway is designed for max speed of 120kph in one paragraph then redefining it as a railway with a top speed of 160kph in another paragraph when it is convenient to his argument. (The latter is correct as China sees it)

Buried somewhere in the middle of this section is what I believe to be the Author’s actual definition of high speed rail: a passenger dedicated railway line with an ultimate design speed of at least 250kph. Which roughly lines up with China’s current official definition. The problem is so much of China’s network deemed “high speed rail” does not properly map to the Author’s definition and the official definition of HSR has shifted around over the years. An example would be the latter inclusion of distinctions such as “express rail” (快速铁路) in the Chinese technical lexicon. Overseas this is better known as higher speed rail and is now in contrast with passenger dedicated +250kph railways officially designated as high speed railways. Before the inclusion of the express rail concept, many older sub-250kph mixed traffic lines were classed as “high speed railways”. Overseas commenters (and the Author) still assume many of these express railway lines have the utility (or limited utility of being specialized only for +250kph passenger services) and design standards of conventional high speed lines.

This is why setting up definitions matter. Just stating “China is overbuilding HSR with 70,000 km of HSR planned by 2035” without context is clickbait when no one knows what is the definition of HSR and just assumes all the HSR lines in question are like the Shinkansen. This is how sensationalist stories of overbuilding sprout up. Is it 70,000km of the fastest top end passenger only French LGV-style lines by 2035 or 70,000km of HSR by 2035 but half of the lines are 200-250kph and some are designed to handle some pretty serious freight and regional services. One is by nature should be optimized for the busiest and most time sensitive travel markets meaning a very narrow utility. The other has a much broader utility and can not strictly be judged only for fast long distance passenger travel.

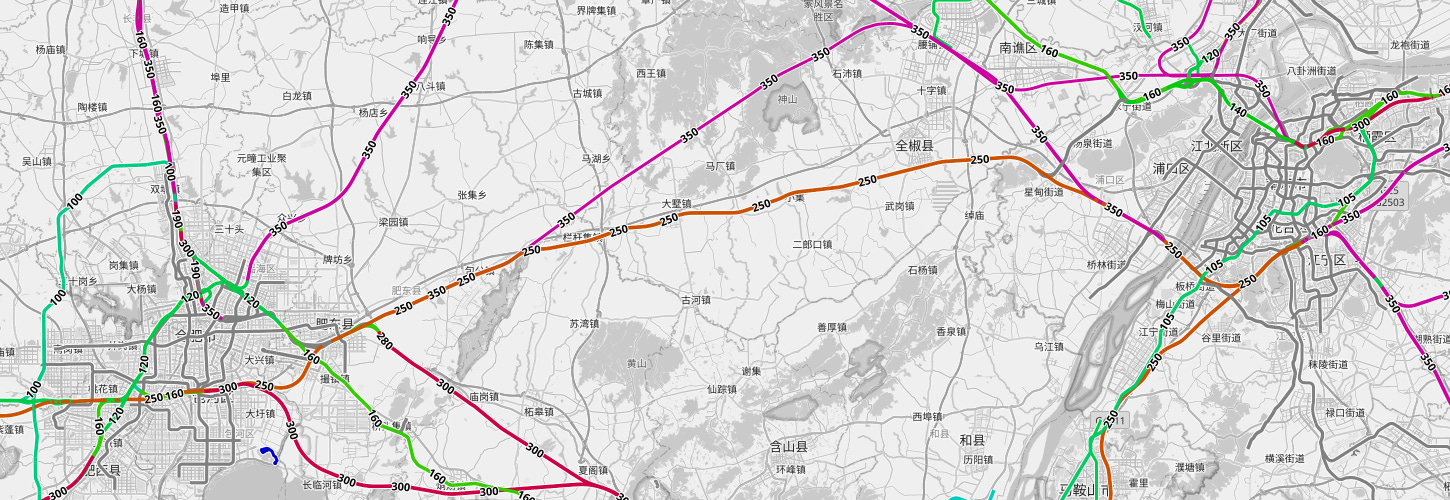

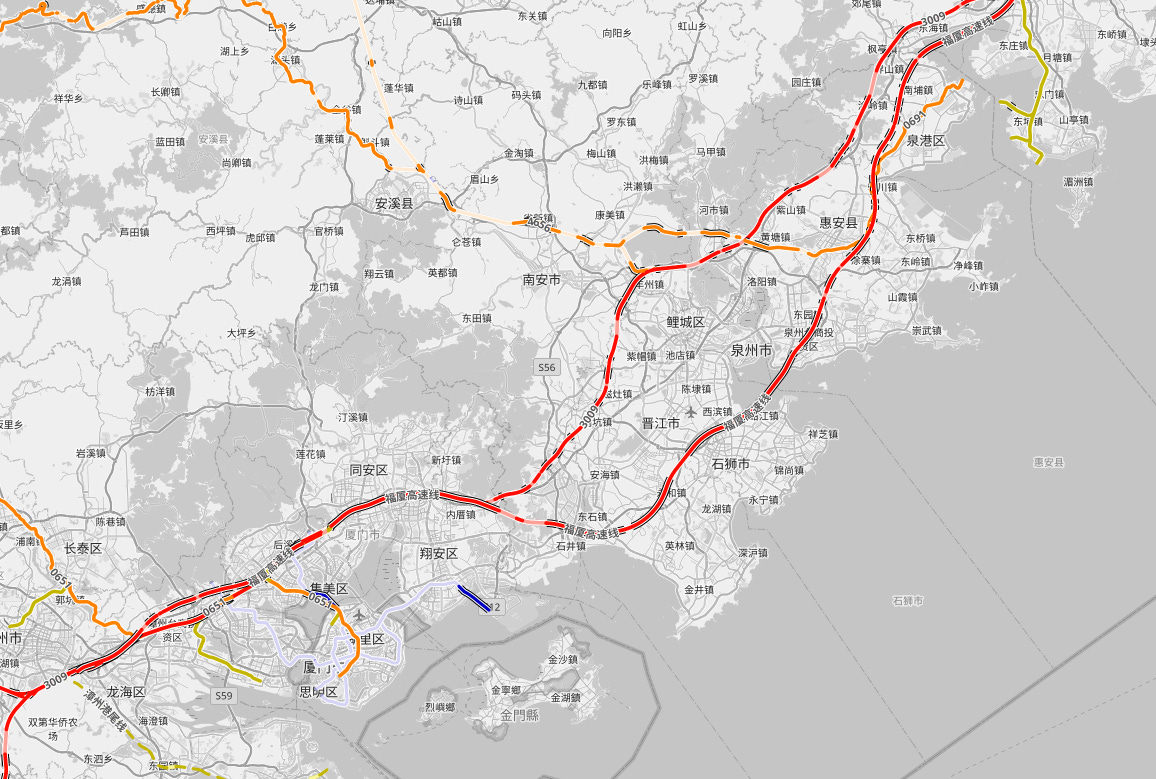

If you look at the Openrailwaymap above off the coast of Fujian north of Xiamen, are there two completely parallel high speed railway lines (labeled red) above? Is this overbuilding? Or is one of the lines a 200-250kph railway capable of running regional and freight services (Fuzhou-Xiamen Railway formerly the Fuzhou-Xiamen High Speed Railway but now designated as an express railway), while the newer one is optimized only for 350kph long haul passenger HSR services (current Fuzhou-Xiamen High Speed Railway). Both statements can led to two different reactions: “Ahhh! overbuilding” vs. “what are the ratio of 250kph to 350kph lines”. Knowing this we can ask about how both these “high speed lines” fit into the network:

Where can we free up capacity to run new freight services?

Is there network wide relief value?

How can regional and long distance traffic be divided up between the two “high speed lines”?

What are potential regional express railway services we can now set up from freed capacity?

Does the extra capacity allow both long distance and regional express railway services be more frequent?

These nuances of railway design and roles are never discussed by the Author in this section. If the Author explored the wonderful flavors and variations of high speed rail that can and does exist in China, I think this section would be an enlightening value add to the conversation. Suggesting China’s high speed rail system is overbuilt and quoting “70,000km of high speed rail by 2035” in the same breath without properly defining what someone can consider high speed rail is misleading on the Author’s end at best, an obfuscation at worse. Again for your information, the answer for what the 70,000 km of HSR by 2035 in China is composed of, the latter is the more correct answer. This has huge implications on the critique of high speed rail network planning that critics seem to miss. But alas the takeaway the Author wants to note in this entire section is: high speed rail is so much more expensive to build and maintain than conventional rail. Which of course dovetails into his whole thesis.

On the planning and construction of China’s HSR

The second section is huge and broken into multiple subsections. The first sub-section “Fundamental principles to be followed in designing China’s HSR network” the Author outlines his principles for HSR planning that are, at face value, pretty reasonable and logical. However he somewhat derails in this section and ends off with a critique on China’s megalopolis rail planning, which in his eyes goes against his principles of high speed rail planning. In his view, there is a risk that government policymakers have been too heavily chasing regional travel time requirements and unnecessarily overusing high speed rail as a mode for middle to short distance regional travel instead of using other modes to fill this role. Again this goes back to the Author’s impreciseness with high speed rail’s definitions and being alarmist about overbuilding. I do not see large amounts of +250kph HSLs in China strictly built to serve only regional traffic. Again there is a definition problem as regular regional “ICR” or express railway or mixed passenger freight “Class I” lines may have some 250kph capable sections and get swept up into China’s high speed rail mileage, making the high speed rail network look overbuilt.

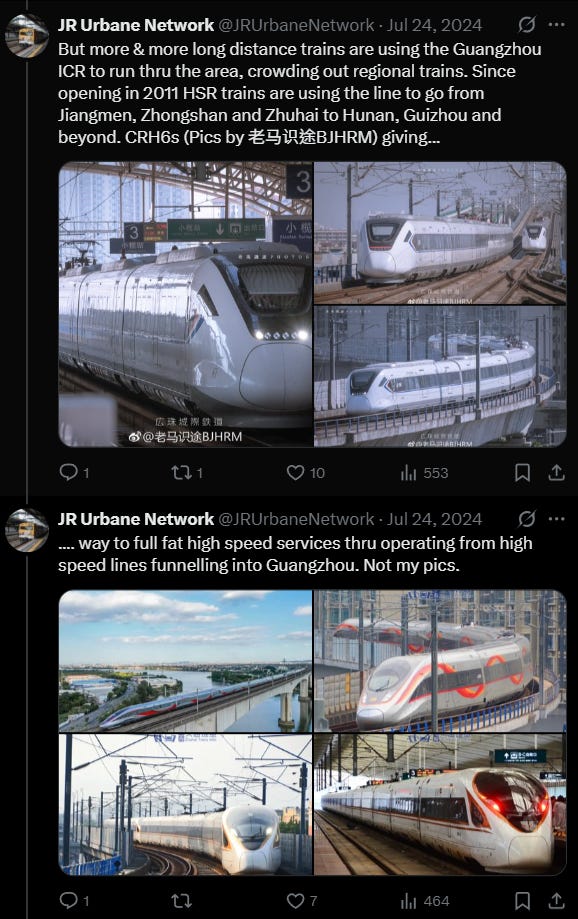

The Author’s issue seems to be with lines like the Guangzhou-Zhuhai or Chengdu-Dujiangyan “intercity” railways or ICRs, which are all regional lines that at times technically fit the broader definition of a high speed railway. Many ICRs have become heavily used for longer distance services instead of their intended regional role. These “successful regional HSRs” clearly are envisioned to be more like a Tsukuba Express on steroids and can be further operated as such. I don’t see how they can be overbuilt. Having a network of frequent semi-high speed regional trains that connect you to a nearby megacity in an hour is not a bad thing.

In fact, for some of these ICRs the solution is to build a parallel higher standard high speed lines to divert long distance trains away from the ICRs to allow for more regional services as those ICRs have become saturated with longer distance HSR trains. These ICRs, if run properly, should serve the mid to short distance market with frequent stopping services as originally intended. However, I’m sure the Author would just say that is overbuilding as there are now two parallel high speed railways in their eyes.

On top of that, many middle to short distance markets in China are being served by high speed metros, not high speed rail, something the Author supports building more of in his Article. However, the translators failed to localize and calls them regional “suburban light rail”. Regardless, with this in mind, the Author should be advocating for China to find ways to run its ICRs and express railways more like regional railways in Europe or Japan not, saying China is building too much HSR for short to medium distance travel, mistaking that many ICR lines are included in the tally.

Basic requirements for HSR planning and construction

This second sub-section, the Author starts with a fairly reasonable (but overused in transport planning, trust me) analogy on network planning using the human anatomy:

“It is said that the total length of blood vessels in the human body is about 96,000 km, while the abdominal and thoracic aorta measures only around 20 centimetres. Though the analogy may not be exact, it serves to make the point.”

It’s clear what is driving the Author’s alarmist stance is his insistence, at a macro level, that China’s overall high speed railway scale is too large and high speed railways should only be used to connect megacities and heavily populated areas. Which I would note, China is blanketed with such conditions (megacities and heavily populated areas) so China should have a large high speed railway network. China’s urban structure also makes his human anatomy analogy not work. Such an analogy only works if there is one “heart” that the “Aorta” feeds into. China clearly is a country with a lot of “hearts” that needs a large network of “Aortas”. Again, the Author seems to be narrowly assuming China’s high speed railway network is entirely made of +250kph passenger only lines which is incorrect.

“Although HSR entails significant capital investment and ongoing maintenance costs, it should only accounts for a small share of China’s total passenger turnover. The majority of land-based passenger transport is undertaken by conventional railway systems, highway networks, and urban public transportation infrastructure.”

These are all obfuscations by the Author. China currently already possesses a large conventional railway system, highway network and urban public transportation infrastructure, all which entails significant capital investment and ongoing maintenance costs. The country is hardly neglecting it’s vast and rapidly expanding conventional railway, roadway, and urban public transportation networks. China today has a:

162,000 km long railway network with 48,000 km of it being high speed railway (How much is express railway?)2.

5.4904 million km highway network (not the same as controlled-access expressway) with 190,700 km of it being controlled-access expressway.

12,161 km of urban rail transit with 9,306 km being metro lines. Nine of the top ten longest metro systems in the world are now in China.3

High speed rail is not (and was never envisioned to be) the bulk of China’s overall transport network (even after all the expansion plans) but a massive integral part of it. The new high speed railway lines provide capacity relief to existing conventional railways that allow the overall network to move more freight or frees up express passenger railways for more regional services. In fact, the Author should instead be actively arguing that China’s expressway expansion be curtailed and funds diverted to his pet projects of more conventional railways and “suburban light rail” not complaining about expanding high speed railways. A lot of urbanists would argue China’s expressway network is overbuilt.

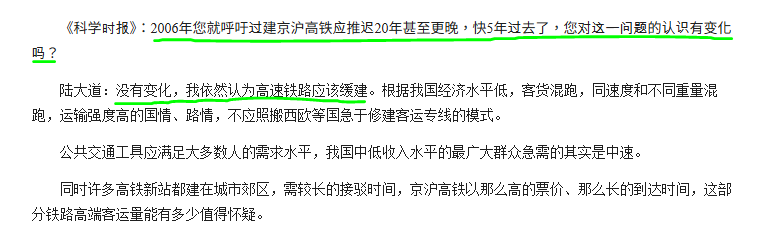

Despite outlining “Fundamental principles to be followed in designing China’s HSR network”. The Author’s personal threshold on what should a viable high speed railway floats unrealistically well above that. Mr. Lu was on the record in 2006 implying the Beijing-Shanghai HSL, today one of the world’s busiest and most profitable HSLs, should have it’s construction delayed for an opening after 2030. In 2006. He further doubled down on that opinion in an interview in 2011:

This is a completely ridiculous track record of conservativism shown by the Author. By this standard, the Tokaido Shinkansen should be the only high speed railway in the world to be built. Ever. The Author’s hardline skepticism on the whole concept of high speed rail remains to this day so a scenario where there is essentially no high speed rail anywhere may not bother him. As shown by a passage later on:

“Why insist on HSR coverage? Numerous countries in Europe and North America have no HSR systems, yet are widely regarded as modern and well-connected.”

This is a silly opinion, and shows how flippant the Author is on transportation planning for high speed rail. These comments are why I think a lot of non-Chinese overseas “transport experts” latch on to this article as “proof” against any high speed railway schemes in their countries. The US or some small European country not having high speed rail is irrelevant and the Author's statement spits in the faces of advocates in those countries (rightfully) arguing for the initiation of high speed rail projects.

“Particularly among relevant authorities and some local officials at the prefectural and county levels, there is a widespread tendency to dismiss conventional railways, some not even bothering to consider them. HSR is proposed even where it is unnecessary; where 250 km/h would suffice, a demand is made for 350 km/h instead. In some cases, parallel high-speed lines are put forward based on dubious justifications. Can these authorities offer a clear and concrete rationale? I believe not. It’s like a child’s game of make-believe—devoid of reason.”

If the Author actually looked at examples of “parallel high speed lines” like the Fuzhou-Xiamen corridor example above or the Wuhan-Yichang (and beyond to Nanjing) corridor examples in the later sections of my post. You can see the nuance that can be had in railway planning. The fact that the Author is light on actual concrete examples shows he has nothing and does not understand the different roles and flavors of high speed railways can take in China. Many new mixed freight passenger express railways that the author claims are “creating” parallel high speed lines are simply just higher performance conventional railways and have a similar utility.

“Policy pronouncements calling for “HSR access for all prefecture-level cities” [There are 293 prefecture-level cities in China, Translator’s note] and “expressway access for every county” lack a sound scientific basis.”

This is a fair critique, not everywhere needs to have high speed railway or expressway access. There is a risk of overbuilding of any infrastructure when such performance metrics are blindly followed. But high speed rail is not the only transport mode that is being pushed by these unscientific KPIs, expressway projects also are appraised in a similar manner, arguably in an even more irrational way. Yet the Author’s body of work (including this article) remains quite silent on that topic compared to his substantial commentary on high speed rail over the years.

“The construction of heavy-haul rail corridors such as the Datong-Qinhuangdao and Shuozhou-Huanghua lines—dedicated to coal transport—effectively resolved long-standing logistics bottlenecks, particularly for Shanxi’s coal exports and north–to-south coal distribution.”

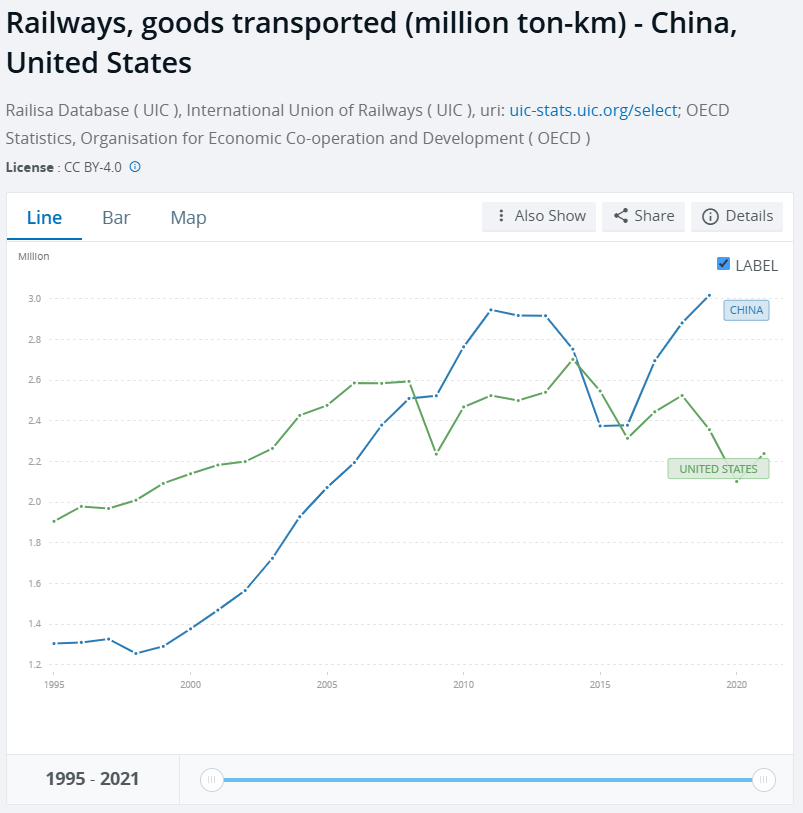

The Author is incorrect in two ways. Firstly, the push for more freight traffic (such as container, chemicals and automobile) to be handled by railways by national transportation outlines this past decade has lead to more demand and congestion on railways. Secondly, the author ignores that the building out of China’s HSR network allowed passenger demands for conventional raailways to fall as existing /new demand used the new EMU services running on the parallel newly built high speed and express railways. The result is the old conventional lines are freed up to carry much more freight. Allowing China to become the busiest freight railway system in the world. high speed rail was what “resolved long-standing logistics bottlenecks” not a few heavy haul coal railways as the Author believes (but those are cool too).

Meme Weeding Sidenote: Where is the Ridership?

At the end of the “Basic requirements for HSR planning and construction” sub-section. The Author notes:

“express services on conventional rail lines remain the most popular, the most heavily used, and the most revenue-generating segment of the network.”

I have to ask, where is the data that supports this? The author pointed out in his long introduction on the history of China’s rapid expansion into high speed railway that:

“Conventional K-series express trains were steadily replaced by EMUs, followed quickly by the grand entry of the HSR era.”

Of course both can be true, the Author seems to be implying that Chinese today are fighting for a dwindling number of Z- and K- series conventional express train tickets and the now plentiful replacement G-, D- and C- series EMU based “high speed” trains are all running empty. This is not the first time such a narrative has been pushed. When China opened its first sections of high speed railway in the late 2000s there was similar critiques internally and aboard that China, at the time a low income country, does not have a market that can afford the higher priced tickets of high speed rail. HSR was criticized as the “white collar railway” in the early 2010s. These critiques died down when ridership on the CRH system exploded as the network was being formed and China’s middle class developed. How in 2025, when China is much richer and more urban(e), this narrative has somehow resurfaced. Detractors could be referencing some recent blogs asserting, Chinese people (all of a sudden?) post COVID can't afford to pay for high speed railway fares and are now clamoring for cheaper, even more heavily subsidized, infrequent, conventional trains. That is not my experience:

Nor does the data support it, over 75% of Chinese railway passenger traffic is carried on “EMU” type G-, D- and C- series “high speed trains” in 2024, which follow more expensive HSR fare rates. Yet total railway ridership today is multiples higher than in the 2000s. The large existing base of high speed railway ridership with exploding ridership growth rates after COVID, now means the CRH system is adding the passenger-km volume of almost two entire Japanese Shinkansen networks every year.

So which is it? Do Chinese people clamor for cheaper state subsidized and almost non-existent conventional rail services and frequent EMU based “high speed” services” services are running empty around the country? As I have noted in the info above, EMU “high speed” services today have insanely high passenger volumes/usage and make up the bulk of passenger railway ridership in China. This is a recent claim being parroted around that “actually all ridership is on the conventional trains”, which as noted above is incorrect, seems to be traced back to people uncritically regurgitating/misinterpreting some recent unsubstantiated info from random blogs published this year (read my Substack, not those blogs).

A new argument that the Author throws in the above quote that I have never heard of to date is the heavily subsidized infrequent, conventional passenger services are huge revenue generators compared to China’s heavily used CRH system, a vast high speed railway network that carries almost 11 million people per day. This is new and unsubstantiated, I have never heard of anyone say the “green trains” are the profit center of China Railways until now. I reiterate, over 75% of Chinese railway passenger traffic is carried on “EMU” type G-, D- and C- series “high speed trains”. Many of these conventional trains “green trains” are viewed as public services for poverty alleviation and are priced as such (read: extremely cheap) but also are not frequent. So I have no idea how the conventional passenger network is the major revenue generators of China Railways according to the Author.

What challenges has China’s HSR brought?

The fourth section is massive and again divided into a few sub-sections, I will skip over the first two and the last two sub-sections named “How did the severe operational losses in HSR come about”, “A brief commentary on the necessity and rationality of the “eight-vertical, eight-horizontal” HSR network”, “How absurd HSR new towns are!”, “Excessive construction of HSR brings a serious debt burden” for a part 2 which is more speculative and subjective as well as diving into more finical and project appraisal aspects of high speed rail. As this post is taking way too long to write and getting too big and unwieldly to read. The third and fourth sub-sections I will dive into to review and comment:

Absurdly located and excessively grand HSR stations

The author uses this section to critique the poor placement of high speed rail stations across the CRH network. There are certainly issues with “suboptimal” placement of high speed rail stations across the country. However, most of the detractors of China’s high speed railway system that bandy around this critique give me some pretty poor examples when I press them on it. Poorly placed stations do exist across China. I have no doubt examples can be found being that China’s high speed rail network has more trackage than the rest of the world combined.

I always view China’s approach to HSR compared to say Japan’s Shinkansen is about tradeoffs in construction and land take costs, average speed, urban access and development potential. I generally do not find the locations of high speed railways in China as bad as some “urbanists” and “railfans” make it to be, mirroring how France and Spain locate high speed railway stations serving their smaller urban areas. I find the debate of the “gare des betteraves”4 style of development that China has, for better or worse, embraced from France and Spain similar to the debate dynamics among advocates between the current California HSR plan and the SNCF proposal for California’s HSR.

The bigger question is: Do these critiques discredit the whole Chinese HSR system? No. The real test will be if these sub-optimalities greatly affect the overall long term viability and utility of the entire Chinese HSR system. In my opinion no. The results (Chinese HSR ridership, mode share, trips per capita and growth) support my opinion. While the Author, media and other hardline critics of China’s railway network expansion continue to grasp at straws with incorrect meme examples they randomly find. They are missing the forest for the trees.

This leads me back to this section of the Author’s article which fall into many of these tropes. Here they spend most of the section listing the same few exaggerated incorrect examples, seemingly getting their information by reading internet forums instead of doing actual economic geography. Exemplified when the Author notes this observation at the start of this section:

“HSR stations in China are being constructed increasingly farther from the cities they are intended to serve, in areas with ever-declining population density.”

This statement is false. Especially with the rapid rise of HSR connection lines to legacy city center stations and “Stuttgart 21” style city center access tunnels being built in major cities across the the country.

“Take, for example, the Beijing–Shanghai HSR, which spans 1,318 km and includes 21 stations. On average, these stations are located about 20 km from the urban centres they are meant to serve.”

I measured the distance of each Beijing–Shanghai HSL station to the city center of the urban area it is supposed to serve5, I got an average of 9km. This is about the distance Taiwan’s HSR stations are from Taoyuan, Taichung, Tainan and Kaohsiung city centers. If you weight it by population the average will drop like a rock as the Beijing–Shanghai HSL stations are quite central in most of the large megacities it serves. This also ignores the fact that closer HSR stations/old railway stations can or will be accessed, French TGV style, by through services via connection lines (such as in Tianjin, Jinan, Bengbu, Changzhou, Wuxi and Suzhou) or that many HSR stations in the major cities on the Beijing–Shanghai HSL are connected to large metro systems some of them the largest in the world. These features (like the critiques) are not unique to the Beijing–Shanghai HSL. Broadly, I do believe China’s HSR stations serving the minor cities can definitely be closer to the urban area (looking at you Dezhou East). However, I do find the critique of poorly located HSR stations overblown (again not that they can not be improved) by urbanist critics.

“Can urban residents genuinely feel “comfortable” after taking overcrowded public transportation and enduring multiple transfers between urban and suburban areas just to reach the station.”

Most trips of any HSR system in the world start and end “enduring” multiple transfers on public transportation networks. Luckily China has some of the world’s largest ones. It is also a bit of an élite projection to assume all/the most important trips of high speed rail are to and from a CBD office center.

The Author goes on to list a bunch of station examples that have become bad internet memes and are mostly incorrect. Making basic geographic mistakes similar to how western media cover China’s HSR system. However, the Author starts the first example with a strong and surprisingly valid criticism.

“Haitou HSR Station in Danzhou, Hainan Province, occupies an area of 4,000 square meters, with a station building covering nearly 2,000 square meters. Yet it has remained unused for eight years since its completion. According to official responses, daily passenger traffic at Haitou Station is fewer than 100 people, and opening the station would result in significant operational losses for the railway authority.”

I do think this example starting out runs into an HSR classification issue. The Hainan West Ring is designed and built as a regional railway. However, being a regional railway with shorter trips last mile access is very important but the line was built to a 250kph standard. A bunch of the stations on that line are poorly placed in hindsight. They are so poorly placed there is a project to refurbish the old conventional railway alignment with new stations which are in better locations.

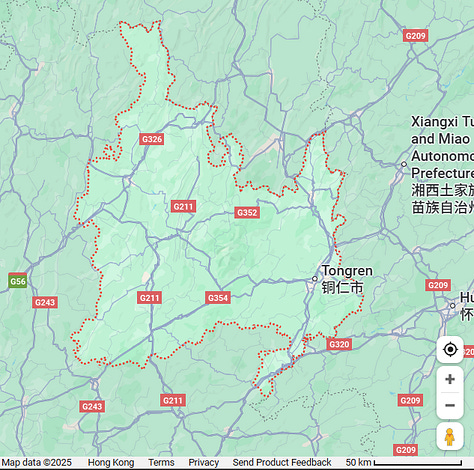

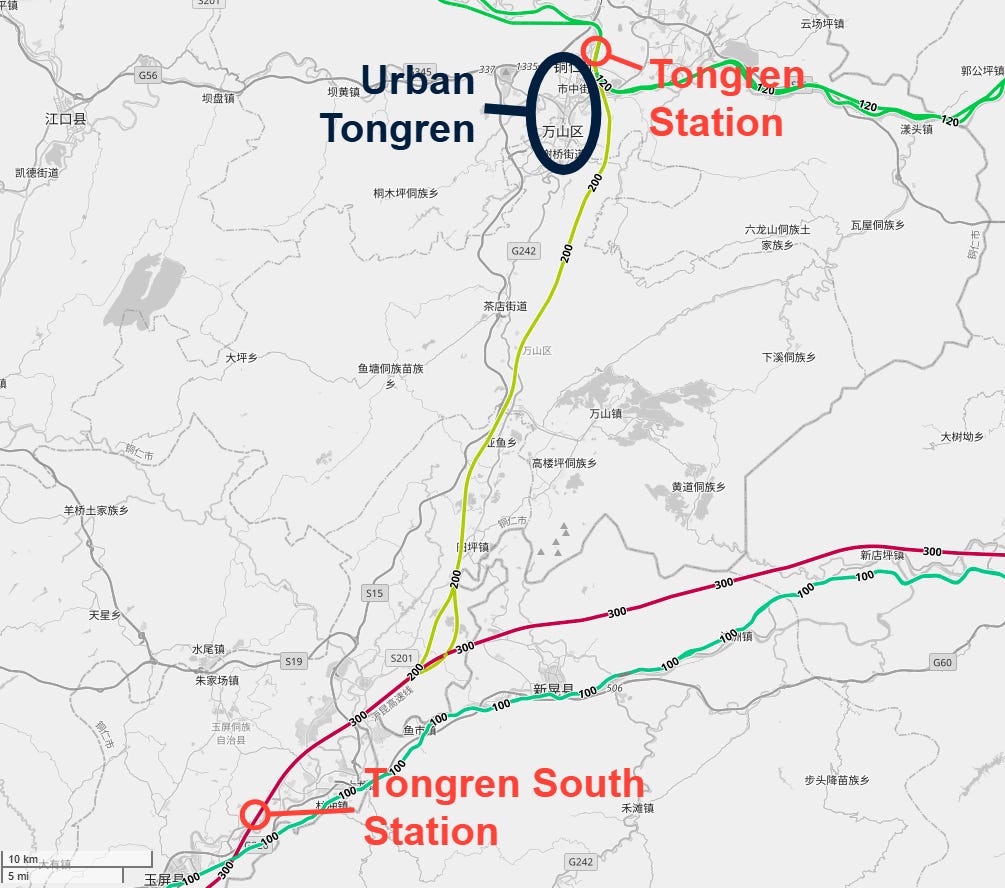

“The Tongren South HSR station in Guizhou Province is located deep in the mountains, 60 km away from the urban area of Tongren. Its building area exceeds 10,000 square metres. For a prefecture-level city of such limited size, reaching the station by taxi takes more than 1 hour and costs nearly 200 yuan.”

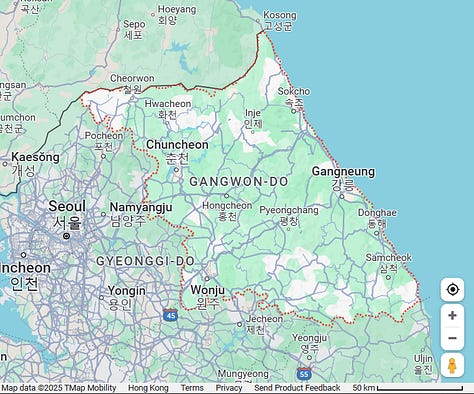

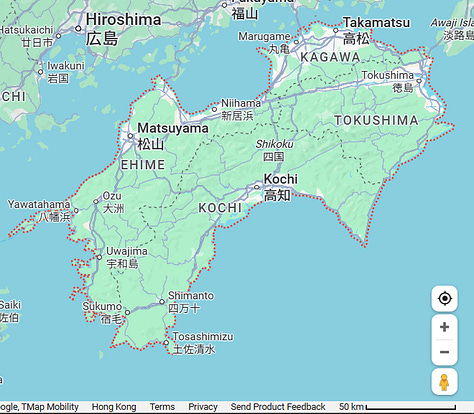

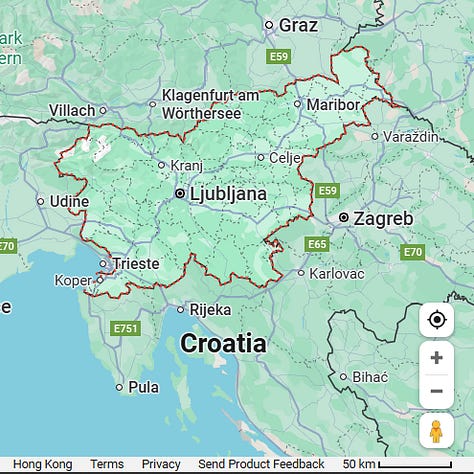

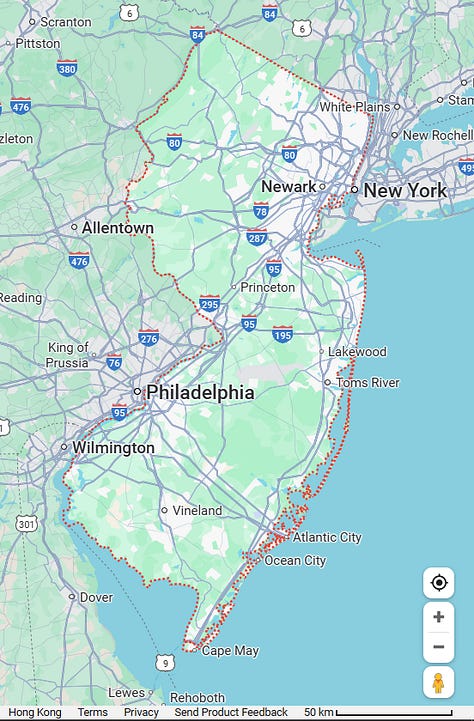

The Author is most likely confused by station naming issues caused by prefecture city and urban core common naming that happens in China. Prefectural cities in China are huge; larger than entire prefectures in Japan and the size of a large South Korean province. However the urban core of that the prefecture is named typically only takes up a small portion of the land area of the prefecture it is in. Tongren “City” is 18,014 km2 (6,955 sq mi) in area, making it larger than any prefecture in Japan (except Hokkaido which is traditionally a circuit that is what the “-do” at the end means) or the size of either two of South Korea’s largest provinces.

To drive this point home, Tongren “City” is the size of the entire island of Shikoku, Japan, almost the size of the entire country of Slovenia and about as large as the state of New Jersey.

Uncritically complaining about how far Tongren South Station is from urban Tongren due an assumed association based on the station name, is like complaining a station in Trenton, NJ on the North East Corridor is bad at serving Jersey City just because it is named South Jersey Station and is still technically in the State of New Jersey. When there are actual stations serving Jersey City proper. No one in Jersey City is taking a taxi to Trenton, NJ to take the train.

Tongren South HSR station is really (and formerly) Yuping Dong Station on the long haul Kunming-Shanghai HSL. This station actually serves the urban area of Yuping Dong Autonomous County of Tongren Prefectural City. It was never designed to serve Tongren’s actual urban core. There is a railway branch line called the Jishou–Yuping Line (Jiyu Railway) that serves the core of Tongren. China Railways should be running regional shuttle trains timed with every HSR arrival (they do not currently do this which is really what the Author should be criticizing) or running branch services from the Kunming-Shanghai HSL to serve Tongren center à la the French TGV (this is being done). There is so much nuance and improvement to be explored but the Author did not think about it because of their “big Chinese HSR scary” thesis. Additionally, one must ask is the 200kph Jiyu Railway connecting urban Tongren to the Kunming-Shanghai HSL HSR? The Author kept hammering home the need for medium distance service by expressways, coach buses or regional “light rail” to improve local connections. However, how would he feel about this line? Is this line counted as part of the “70,000 km of HSR by 2035”? It would be classed as an express railway today. No one knows what counts as high speed rail.

It is clear that the 350kph Shanghai-Kunming HSL (rightfully) prioritized speed and as-the-crow-flies directness between the big cities of China. This is not unique to China, the core planning ethos of the French TGV is to build direct fast lines between the major cities, with branch lines to access the smaller towns. To similarly achieve what the French did, the Shanghai Kunming HSL avoided the out of the way Tongren urban center but did not sacrifice connectivity/access as there is the Jiyu Railway branch line serving Tongren urban center.

Access to all local communities vs direct rapid mobility dynamic between the biggest cities (with construction cost considerations sprinkled in) in HSR planning is similar to the fabled French SNCF proposal for California’s HSR project. SNCF allegedly proposed a more direct HSL main corridor between San Francisco and Los Angeles with lower speed access branches to smaller towns in the valley (the Bakersfield’s, Fresno’s and Merceds’). This is in contrast with current alignment of the Initial Operating Segment (IOS) on the California HSR that hits the centers of all the minor towns in the San Joaquin Valley. Except now that the tradeoff being discussed here involves China, the discourse is somehow even less intelligent. In this example, infrastructure for station access is not an issue, the service is, but the Author made no note of this and incorrectly assumes Tongren South is a great example of how China builds high speed railway stations too far from population centers.

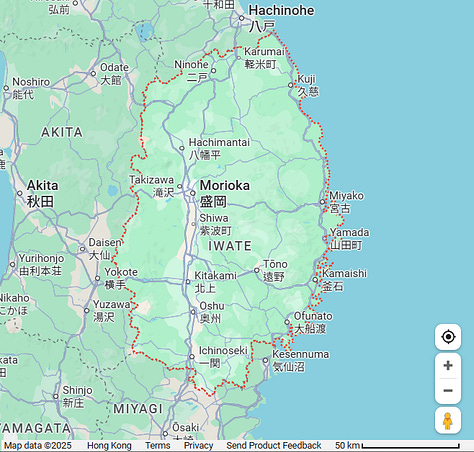

“Xiaogan North Station, designated a First-Class Station [the second tier in China’s six-level station classification system, which is intended for facilities handling more than 15,000 passengers per day], was built at a cost of 120 million yuan. Yet on most days, it serves just over a hundred passengers, fewer than the number of staff who operate it. Strikingly, the station is located nearly 100 km from the city’s urban area. Unsurprisingly, unless absolutely necessary, local residents are unwilling to spend one to two hours to reach the station in order to board a high-speed train.”

The Author definitely got this example from the four great mythical north stations (四大神北) internet meme about far flung stations. The station actually serves Dawu County of Xiaogan Prefectural City, more specifically the largest town in Dawu County and its town center is only 9km away.

The author is correct, no one living in urban Xiaogan would travel to Xiaogan North Station, a station that is almost 100km away, to board a high speed train. No one is that stupid. Urban Xiaogan residents have their own HSR station to use right in the city center.

Again the author forgets, Xiaogan Prefectural City has a land area of 8,923km2 (3,445 sq mi) with over 4 million people scattered across. You can have multiple high speed railway stations serving such a large area.

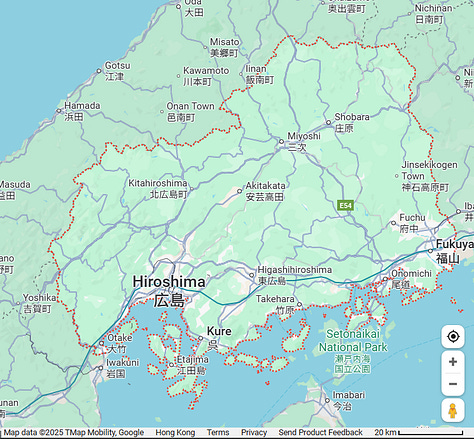

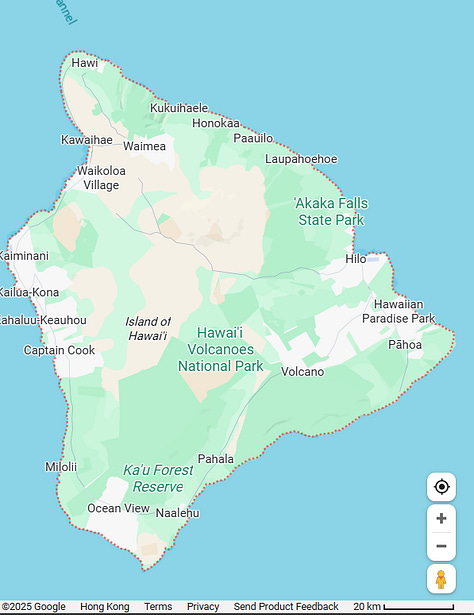

The land area of Xiaogan Prefectural City is similar to that of Hiroshima Prefecture and slightly smaller than the entire island of Hawaiʻi. Is anyone from Hiroshima City going to Fukuyama Station, which is still in Hiroshima Prefecture, to take the Shinkansen?

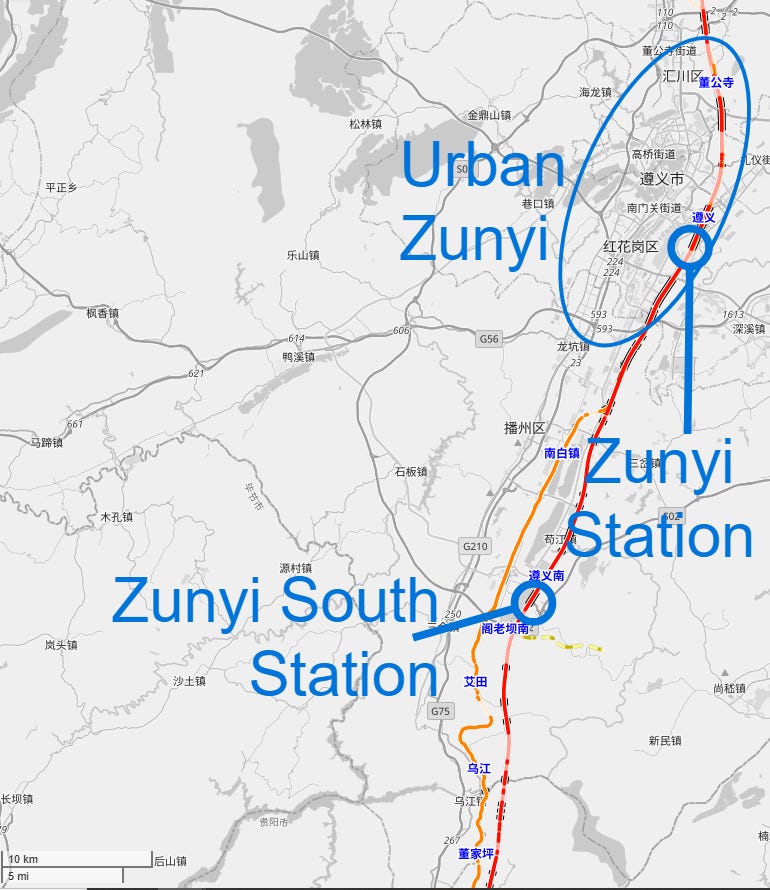

“According to online reports, reaching Zunyi South Station from the urban area of Zunyi can take passengers up to three hours by public transportation.”

I do not know why this lone sentence was nonchalantly thrown in this section as an aside. This is just one example inserted into the text and has no expansion on its ideas. However, the mistakes are the same and I reiterate, the Author picking stations that are really meant to serve other towns in a massive prefectural city of Zunyi (land area of 30,763 km2 or 11,878 sq mi) which is the size of the Canadian Province of Newfoundland AND Labrador, larger than the US state of Maryland, or spanning the entire country of Belgium. In addition, actual stations that serve the urban core of Zunyi exist, such as Zunyi Station 30km north of Zunyi South Station. Get this, Zunyi Station is on the same railway line and served by the same (or even more) trains. This is really poor research on the the Author’s part.

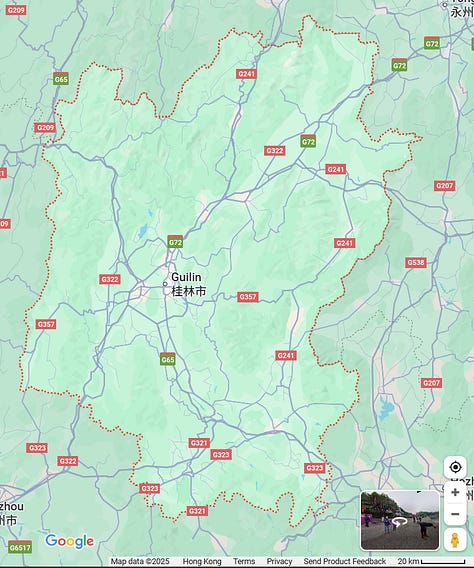

“Astonishingly, Guilin has constructed nine high-speed rail stations—enough to resemble a metro grid or a network of bus stops.”

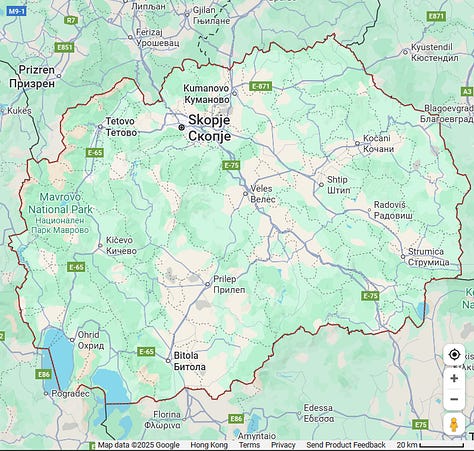

Again another random sloppy single sentence example. The Author is performing poor geographical analysis, Guilin Prefectural City is 27,797 km2 (10,732 sq mi) in land area which is the size of the European country of Macedonia or the US State of Massachusetts. Is nine stations too much?

Additionally, how many “high speed rail” stations in Guilin Prefecture are for serving a 300kph passenger dedicated, actual high speed line? I see of the nine stations in Guilin Prefectural City the Author counted as “high speed rail” some are on Class I railways (Hengyang-Liuzhou Railway) that support 250kph operations but are also designed for regular locomotive hauled conventional railway services and can even carry freight transport. Again a definition problem, what is high speed rail? The Author is not being consistent with his definitions of high speed rail.

“Huizhou City, with a land area of 11,000 square km and a GDP of 560 billion yuan in 2023—over 60% of which came from exports, primarily in small- and medium-sized manufacturing—has nonetheless built nine HSR stations.”

The author said it themselves, Huizhou Prefectural City is almost the size of the US state of Connecticut or the European country of Montenegro. When you now have that perspective, is nine HSR stations too much? Niigata Prefecture has eight HSR stations and is smaller than Huizhou Prefectural City in population and slightly larger in land area. Huizhou is part of the booming Pearl River Delta urban megalopolis. Niigata Prefecture is not any of these things. Again these observations and comparisons the Author is making are nonsensical.

“These [stations] were intended to serve trains arriving from Zhejiang, Fujian, and eastern Guangdong. However, given Huizhou’s proximity to Guangzhou—only about 30 km away—the number of scheduled services from these directions is already limited.”

Firstly, Huizhou is not 30km from Guangzhou, it is over 110km city center to city center as the crow flies. I have no idea where the Author got the 30km that distance from. Regardless 110km is approximately the distance between Nagoya to Kyoto, Nagoya to Hamamatsu, Tokyo to Fuji City, Tokyo to Utsunomiya, Tokyo to Takasaki, Fukuoka to Kumamoto, Daegu to Busan, Tainan to Taichung. All these pairs of cities are logical HSR trips, even when there are parallel local conventional train services. I had a friend from Europe who wanted to go from Guangzhou to Huizhou to see a Chinese replica of Hallstatt and guess what they took? HSR. Said it was great. Again poor understanding of Chinese prefectural city boundaries (and basic geography) are hampering the Author’s analysis.

Secondly, there are a lot of scheduled services at Huizhou heading to and from Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, eastern Guangdong and beyond. There are around 50 trains a day per direction stopping at the newly opened Huizhou North, over 60 trains per day per direction at Huiyang Station and around 30 trains per day at also the newly opened Huizhou South.

The Author, by erroneously believing that Huizhou is 30km away from Guangzhou, is implying that passengers from Huizhou should simply go to Guangzhou via local public transit and transfer to high speed trains to get to other parts of China. However this is hypocritical as the Author previously has obliquely critiqued China’s outlying HSR stations by rhetorically asking in the beginning of this section:

“Can urban residents genuinely feel “comfortable” after taking overcrowded public transportation and enduring multiple transfers between urban and suburban areas just to reach the station?”

By arguing for less coverage of HSR stations in Huizhou due to perceived proximity with Guangzhou/Shenzhen the Author is forcing Huizhou urban residents into “taking overcrowded public transportation and enduring multiple transfers between urban and suburban areas just to reach the station.”

“How many passengers are actually boarding or disembarking at these nine stations within Huizhou?”

Based on my experience, a lot of people use Huizhou’s HSR stations. Below is outside of one of those stations, Huiyang Station on the busy Shenzhen-Xiamen line an express railway line. As you can see it was a busy zoo of activity on a normal Sunday:

I think Huiyang Station is quite well used actually:

“By contrast, Chongqing East Station is situated in the Chayuan New District on the city’s southern bank, far beyond the established urban core, in an area with a scattered population.”

Chongqing East Station, being a massive newly opened railway station, is catching extra scrutiny due to recently bias, not because there are genuine critiques. Chongqing East Station is only 10 km away from Chongqing city center and today it takes 23 mins on the existing Line 6 metro line to get to the city center. In the future it should take just 10-15 mins to get to the city center via high speed metro Line 27, especially if you get an express stopping pattern. The Author also ignores a massive Stuttgart 21 style cross city underground railway that will allow high speed trains to access the city center Chongqing Railway station from Chongqing East Station or is that project also overbuilding in the Author's eyes because it is a short segment of high speed railway?

Extensive construction of short-distance HSR: economic losses, even severe losses, are inevitable

The Author uses this sub-section to criticize the emergence of “mid to short distance“ HSR lines that have been appearing across China as of late.

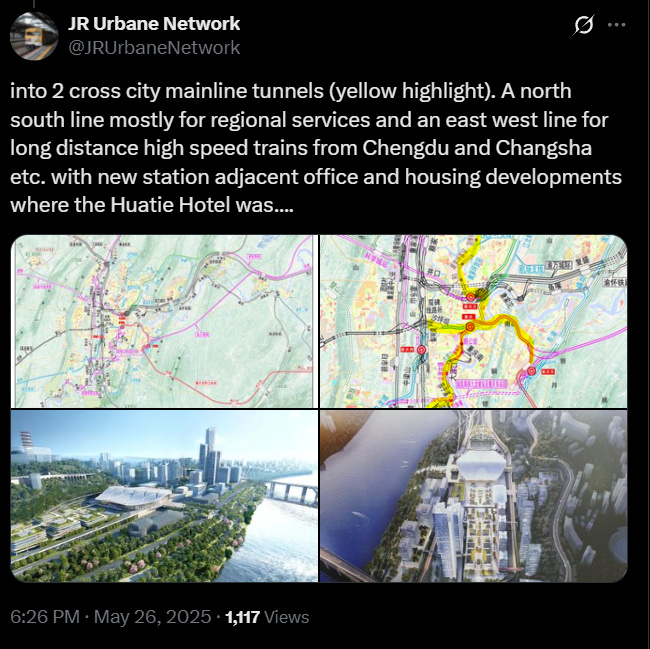

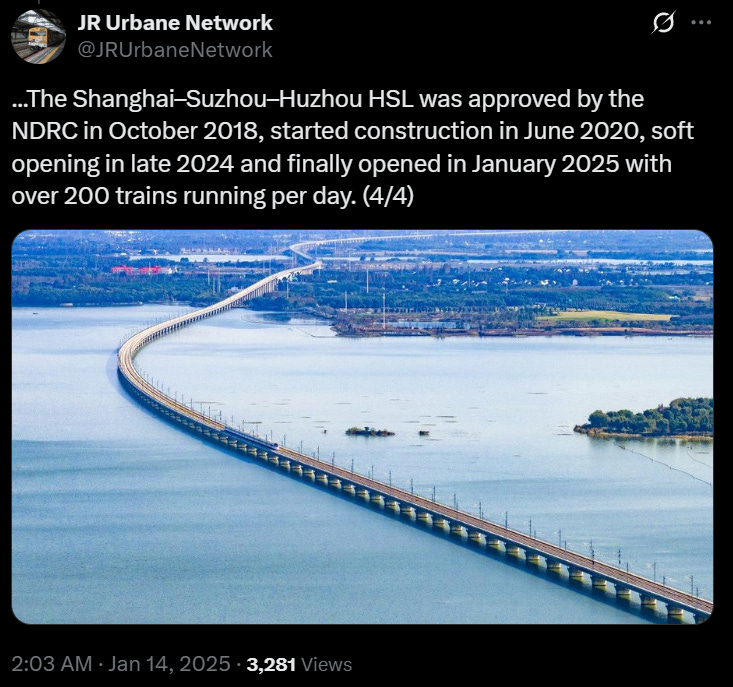

“Within city clusters, in areas surrounding central cities, and among some medium-sized cities, a new wave of “short-distance HSR (most under 200 km) fervour” has emerged. Examples include the Shanghai–Suzhou–Huzhou HSR; the Shenzhen–Nansha (Guangzhou)–Jiangmen HSR; the ongoing large-scale Guangzhou–Zhanjiang HSR project in the Pearl River Delta; and in Hubei Province, eight HSR lines are currently under construction, including the Jingmen-Jingzhou HSR, Wuhan–Yichang HSR, Xiangyang–Jingmen HSR, and the Xi’an–Shiyan HSR. Chengdu and Chongqing are also planning similar short-distance HSR routes radiating from their urban cores to nearby medium-sized cities.”

I recognize the official justifications and framing of these projects the Author highlights above emphasizes a “short distance” regional role at face value. However, upon completion of these projects or a closer examination of future plans, it is clear many of the projects have big network implications which, regrettably, the Author misses. Being built to mainline standards these projects must be examined on their improvements to the overall railway network they connect to. When analyzed with the broader network in mind, the Author's examples and critique mostly fall flat.

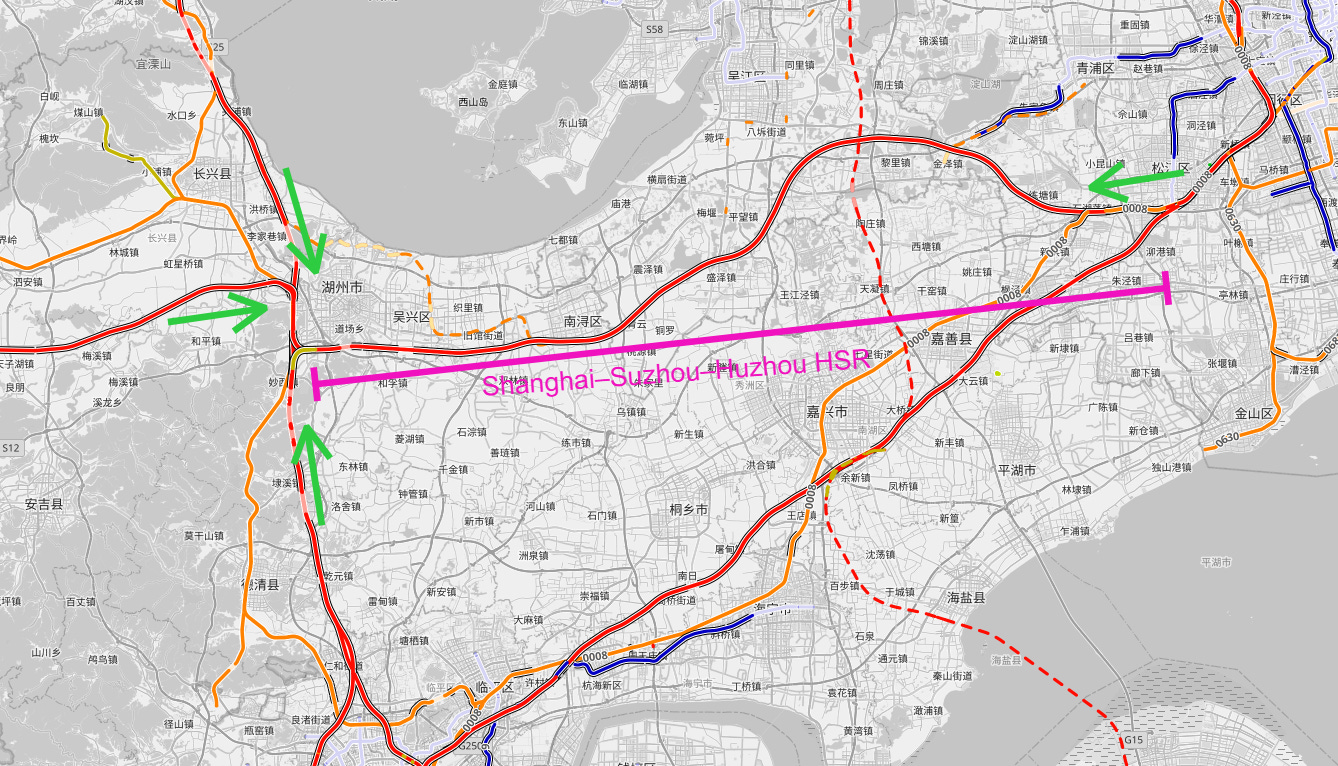

The Shanghai–Suzhou–Huzhou HSR is a connector line that allows long haul HSR services to and from Shanghai to bypass Hangzhou and access the rest of China.

As of 2025, there are 114.5 pairs of high speed trains running on this few months old line each day. The services on this newly opened line are not shuttling back and forth 160km between Shanghai and Huzhou but heading to Nanjing, Anhui and beyond. The physical line may be short but the services using it are not.

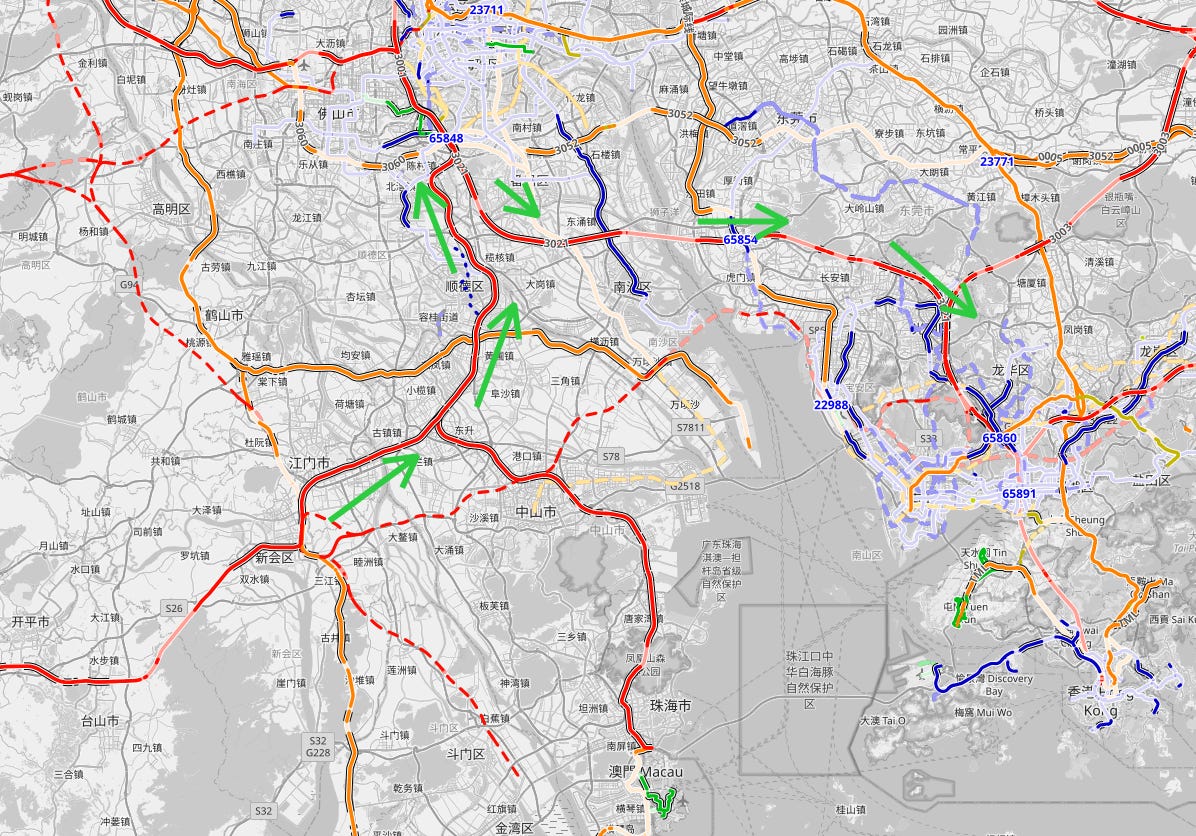

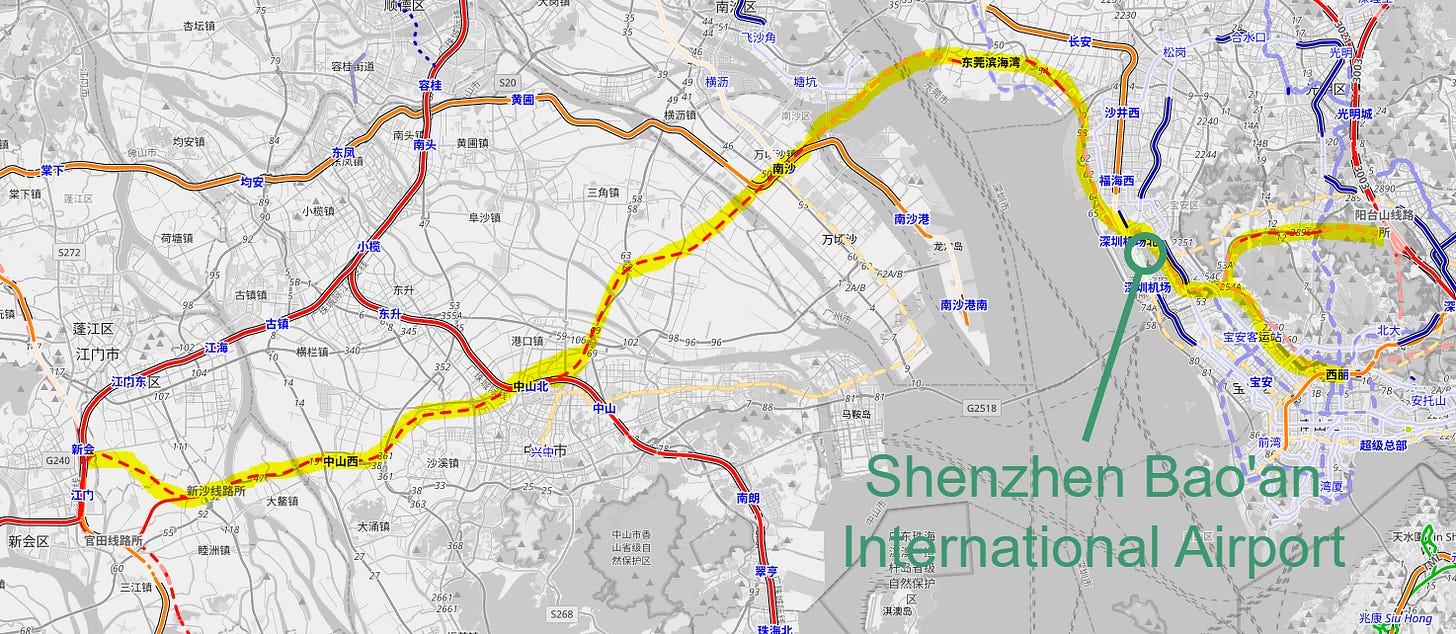

Shenzhen–Nansha (Guangzhou)–Jiangmen HSR is an extremely important bypass line that will unlock the congested Guangzhou-Zhuhai “ICR” regional railway which has been “dominated” by long distance HSR services that crowd out regional mid-distance services.

The Shenzhen–Nansha (Guangzhou)–Jiangmen HSR will allow the Guangzhou-Zhuhai ICR to actually provide actual regional railway services and allow 2 “abandoned” HSR stations to be reactivated for local services. I will remind you the Author was advocating China provide more regional mid-distance services, freeing up the Guangzhou-Zhuhai ICR from long distance through traffic achieves that. This line also allows high speed railway services to directly connect to the massive and busy Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, part of an emerging trend in China to provide HSR access to its airports.

In addition, to decongesting the Guangzhou-Zhuhai ICR the Shenzhen–Nansha (Guangzhou)–Jiangmen HSR will allow services to avoid reversing movements in the busy Guangzhou South station and decongest the Guangzhou-Shenzhen HSL which is one of the busiest high speed railway lines in the world, with a passenger-km ridership intensity exceeding that of the Tokaido Shinkansen.

So I'm not sure what the Author is saying about this line being of questionable utility? I would like a high speed service directly going from Hong Kong to Jiangmen, Zhongshan and western Guangdong. I’m sure allowing any high speed train anywhere from Guangdong Province to reach Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport is a good idea. It decongests the busy Pearl River Delta HSR network and allows for more trains to go from Hong Kong to the rest of China, more Fujian Province trains to go to Guangxi Province or more Macau/Zhuhai trains to reach Jiangxi Province etc. Again the Author needs to have network thinking and not focus on the fact that the line is 116 km long, it is connected to a railway network on both ends

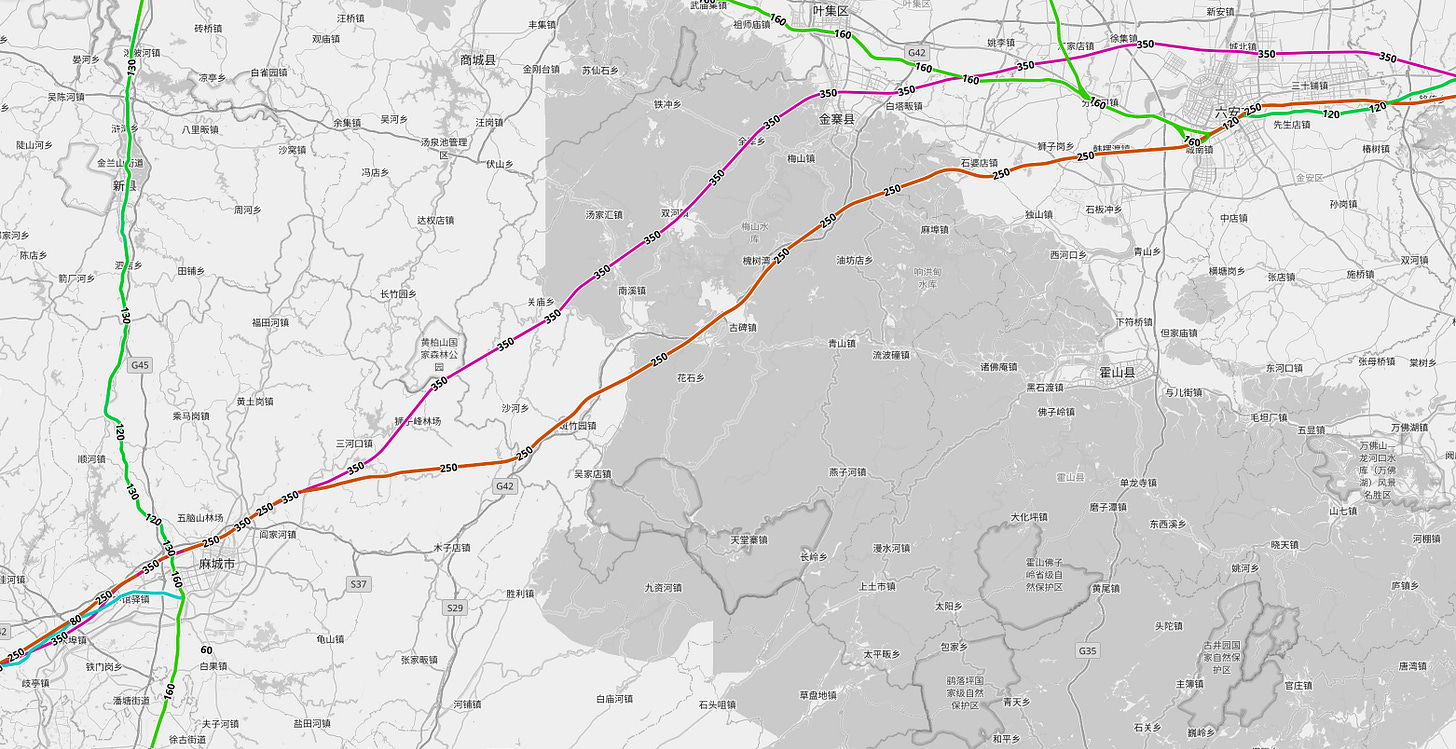

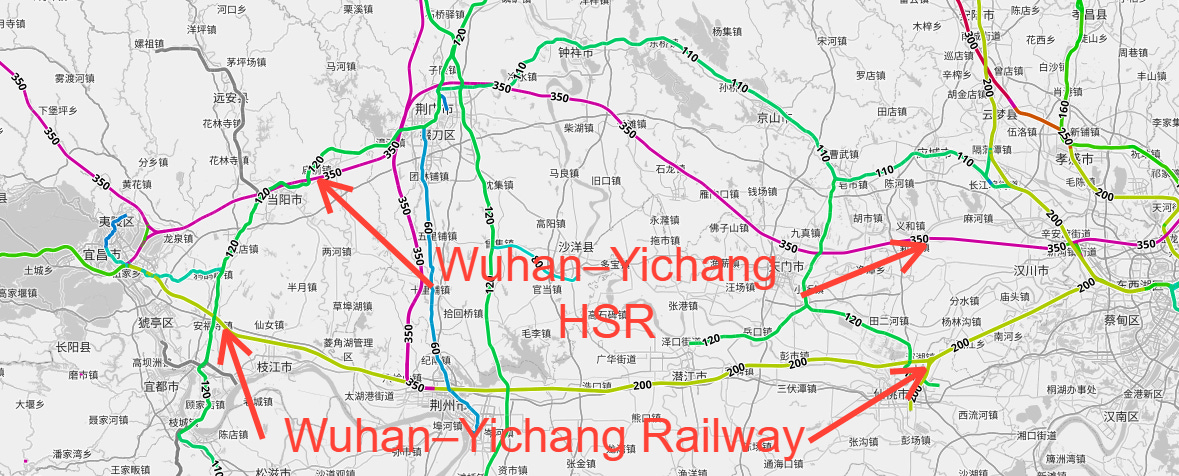

Wuhan–Yichang HSR is a new HSR that parallels the “old” Wuhan–Yichang railway. However the Wuhan–Yichang Railway was built to Class 1 standards that accommodate mixed freight 120kph and passenger 200kph operations. Originally the line, like the rest of the existing Chongqing-Yichang-Wuhan-Hefei-Nanjing corridor is a 200-250kph is a mixed traffic HSR corridor of the national 4+4 HSR grid plan (what even counts as HSR in China again?). Apparently this existing corridor can support double stack container operations and some pretty serious freight operations.

The Wuhan–Yichang Railway currently sees such heavy passenger use that minimal freight traffic can be slotted into it. Regardless, these are the passenger priority regional railroads that can carry freight and locomotive hauled conventional services that are important for China which are disguised as HSR and are now approaching capacity despite kicking out most of the freight traffic.

There are two issues with the Author’s example:

The Wuhan–Yichang HSR dedicated to the needs of passenger traffic. As such it is rated for 350kph and allows for capacity relief of the older railway. The “old” lower standard Wuhan–Yichang express railway can then be focused to carry freight and short regional trips while the long haul Chongqing to Wuhan (and beyond) trips can use the new 350kph Wuhan–Yichang HSL bypassing the “old” 200-250kph mixed traffic express railway.

The Wuhan–Yichang HSR is not a short isolated HSR line but part of a broader full 350kph under construction Chengdu-Nanjing-Shanghai long haul HSR corridor that will parallel the existing congested “old” mixed freight 200-250kph HSR Chengdu-Nanjing-Shanghai express railway corridor.

Again the Author’s lack of network analysis is really showing here. It is not a short HSL with trains shuttling back and forth. The project provides capacity relief and release for the older, slower railway corridor that also could carry freight traffic. We must again ask, what is high speed rail? I reiterate, yes these are parallel “high speed lines” but can have clear roles in the network.

Xi’an–Shiyan HSR is the last segment of a diagonal Wuhan-Xia’n HSL that allows for connections between Wuhan (武汉) and Xi’an (西安). This line will reduce train travel times between two massive +10 million population megacities of Wuhan to Xi'an from five hours to under three hours by not having services travel in a right angle L via Zhengzhou (郑州). This will also decongest and de interline the congested Wuhan-Zhengzhou and Zhengzhou-Xi’an HSLs.

I do not know why the Author brings this example up as the line is clearly a segment of a longer multi-phase long distance line. Again, really poor analysis using silly examples based on a flawed premise that does not show any network thinking what-so-ever.

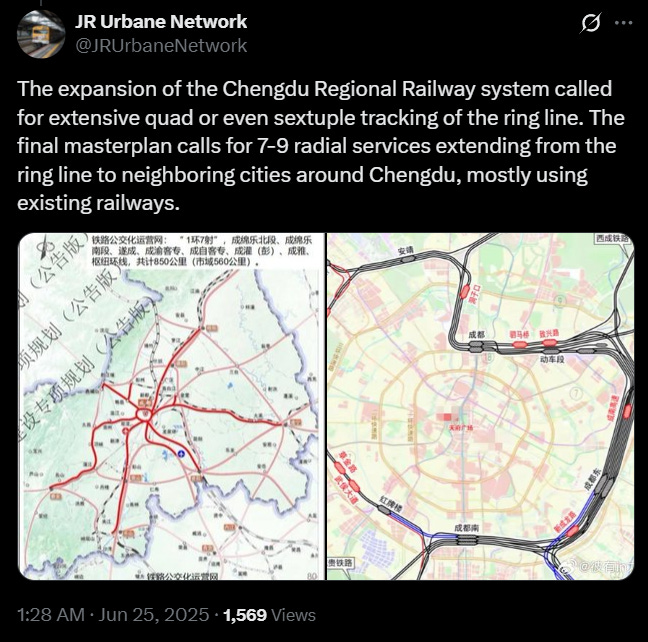

“Chengdu and Chongqing are also planning similar short-distance HSR routes.”

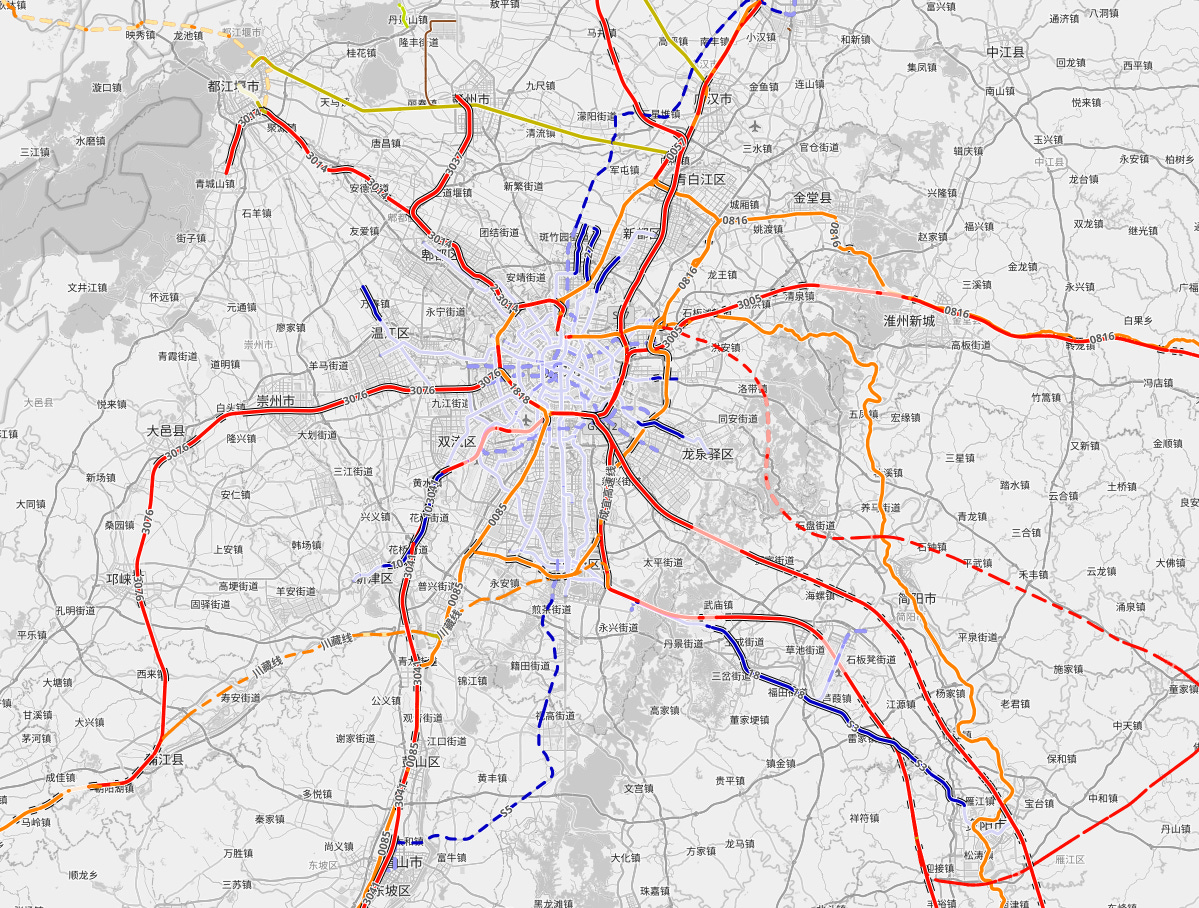

These lines are rated for 200-250kph (again HSR definition problem) designed for high frequency with tighter more urban(e) stations and are now being transformed into a large regional railway network with trains up to every 10-20 mins to each neighboring city:

I will end off this section reiterating, the “short-distance HSLs” the Author complains about are connected to the broader railway network so a more comprehensive holistic analysis is required. Criticizing them as being too short to be viable/not a good use of the HSR mode is the equivalent of criticizing the last crucial segment of expressway connecting/finishing off the broader network as “too short” to be viable due to its short length. This whole section the Author wrote is flawed from the start.

I will skip over Section 5 which is “What are the causes behind the HSR’s problems?” and the Authors conclusions written under a sixth section “My suggestions”. Both sections deal in more subjective issues or financial considerations which I think I will cover it in a later part 2 (or even Part 3).

Additional Notes: Where the Author goes insane.

The last part of the Article the author provides an “Attachment to this article” called “critique of the development Maglev Train: The “Chinese Concorde” that should be Cancelled!” The Author goes insane. First noting:

This February, at a spring seminar of a well-known forum, a senior engineer from China’s railway establishment delivered a report on the development trajectory of the country’s high-speed maglev programme. Rather than addressing pressing and important questions such as how to utilise the 70–80% idle capacity within the vast HSR system

I can’t find where the Author got that the CRH system is 70–80% idle (sitting in the sun as he colorfully described it) I’ll assume it is the start of his madness. Or a combination of not knowing what counts as HSR, sloppy analysis and not knowing how networks work as I have extensively wrote above. The Author continues arguing that maglev is not needed as “many of these impressive HSR lines and stations are severely underutilized or essentially idle. To put it more bluntly, they are abandoned.” Again all incorrect. See this post. However, the Author then notes:

The strong electromagnetic radiation generated during maglev train operation adversely affects the surrounding environment and the health of nearby residents. This is one of the reasons why maglev technology has not been widely promoted either in China or globally.

I’m sorry, I can not take anyone that earnestly believes in this unscientific drivel cooked up by bored middle class NIMBY housewives in late 2000s Shanghai. I think I’ll end off here. This last segment really tells you all you need to know about how knowledgeable the Author is on these matters, you can ignore everything else I wrote above and more importantly ignore what the Author writes.

Conclusion

In this part 1, I focus on the technical issues the Author makes because I would like the criticism of Chinese HSR system (there is a lot to critique) to be better, more informed and more specific, that is what constructive criticism means. Anyone can just wave their hands around and vaguely say “That looks too big.” or “I just don’t see the value in all of this.” I reiterate, China’s HSR system is not perfect but I would like the discourse to be a discussion on the genuine cost, access, speed and service design tradeoffs and considerations. Regardless, unlike what the Author believes, the CRH system is a broad positive implemented in a suboptimal way for some aspects as noted by Reece of Next Metro/Cinq Personnel's fame:

I would even go a step further and consider China’s HSR system to be largely successful.

Funnily enough the Lu Dadao’s name can be interpreted as 陆 = land 大 = great/big 道 = corridor/way/path, he is literally Mr. Land Transportation.

I believe in this case HSR is defined as lines capable of reaching 250kph.

The longest metro systems in the world as of October 2025 are:

Shanghai/Suzhou (1,155 km)

Guangzhou/Foshan (860 km)

Beijing (838 km)

Shenzhen/Hong Kong (792 km)

Chengdu (633 km)

Hangzhou/Shaoxing (624 km)

Greater Seoul (579 km)

Chongqing (560 km)

Nanjing (557km)

Wuhan (518 km)

French for “Beetroot Station” or beetfield stations used by transit commentators describing the tendency for French TGV stations to be built in outlying rural areas for minor cities.

If the city had multiple centers I used the closest one.

Thank you for this fabulously detailed account of China’s HSR system.

like to add a simple point - anyone these days would much prefer to hop on a hsr and go from, for example shanghai to beijing, than head to the airport and suffer interminable delays.

the amount of gross negligence in the article you are responding to gives cause to wonder - just why??

Excellent piece that sums up much of where my head was at when reading the original article.

I do think the strongest criticism is related to “absurdly located and excessively grand HSR stations”. I understand the imperative need at times for the former bit, but in many locations connectivity can absolutely be improved between the station and the historical urban core. Off the top of my head, Panzhou —> Xingyi and Zhaoqing East —> Zhaoqing are intimidatingly far with poor connectivity, but there are certainly others.

In Kunming, some trains still go from the old train station, and there are numerous trains that run from Kunming South to Kunming Station. I would be interested in knowing what would be holding Guangzhou South back from having the same connectivity to Guangzhou? It takes almost an hour to get into Guangzhou on the metro currently - at the very least, they should absolutely consider express metro lines.

Lavish stations are another fair critique, though for the most part it seems like many of the worst offenders there opened around the early 10s. Off the top of my head, Wuzhou and Taishan both seem quite overbuilt, but there are definitely others. I suppose time will tell with regards to the station in Chongqing cited in the article, but some skepticism is probably warranted.